|

Keratoconus

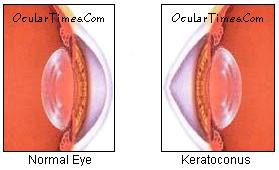

Keratoconus (ectatic corneal dystrophy) is an eye condition in which

the shape of the cornea bulges and becomes conical

(cone-shaped), resulting in thinning and eventual

scarring of the central cornea. The disorder affects

women more often than men, and occurs more frequently in

patients with Down's syndrome, Marfan's

syndrome, Addison's disease, neurofibromatosis,

allergies, and congenital amaurosis (a rare form of

blindness at birth).

Symptoms

Keratoconus

is characterized by thinning and protrusion of the

central and/or paracentral cornea, resulting in corneal

distortion, photophobia, halos around lights, decreased

vision, and monocular diplopia (double-vision).

Indicative warning signs of early keratoconus include

frequent eyeglass prescription changes associated with

progressive myopic astigmatism.

The onset of

keratoconus occurs predominantly in the late teens.

Symptoms usually appear bilaterally, but it is not

uncommon to have an asymmetric presentation. During the

first 5-7 years of onset, the condition generally worsens

with intermittent periods of remission. In many cases,

the degenerative process stops as the patient reaches his

or her 40s. The first eye affected typically suffers more

severe consequences, while the second eye may not show

any signs until years later, if at all.

On clinical

examination, patients with keratoconus may produce a low

intraocular pressure (IOP) reading. This is due to

corneal thinning and/or reduced sceral rigidity, either

of which can cause a reduction in corneal tension on

tonometer applanation.

Causes

Various

theories have speculated that biochemical abnormalities

may be responsible for the development of keratoconus.

Recent studies have shown that abnormalities in

proteoglycan metabolism have been associated with

keratoconic corneas. Abnormalities in collagen fiber

cross-linking have also been documented. There also

appears to be some association with certain systemic

diseases (see above).

Another

theory is that keratoconus represents a degenerative

condition attributed to corneal stress factors. Studies

that support this theory note that keratoconus develops

more often in persons who have a history of recurrent

ocular surface irritation secondary to long-term contact

lens wear and chronic vernal conjunctivits.

The role of

heredity in the development of keratoconus has not been

clearly established. Although genetic inheritance of the

disorder has been noted, the majority of the cases show

no definitive inheritance pattern. In some cases,

however, genealogical analysis suggests a sex-linked

autosomal dominant mode of inheritance, particularly

because of the predominance of familial females with

keratoconus

Diagnosis

Early

keratoconus usually manifests as a small island of

irregular astigmatism in the inferior paracentral cornea.

As the cornea bulges outward, the amount of astigmatism

increases due to the progressive distortion of the

corneal surface. These changes can easily be seen as

irregular mires on keratometry readings and on corneal

topography, a test used to map the topographical

surface area of the cornea.

Munson's

sign - On physical examination, Munson's Sign

is readily observable without the requirement of

sophisticated testing equipment. As the patient gazes inferiorally, the apex of the cone angulates the lower

lid outward, forming a 'V-shaped' protrusion. Milder

signs of Munson's may be more easily seen when the head

is tilted slightly back and upper lids are lifted while

the patient gazes downward. Munson's

sign - On physical examination, Munson's Sign

is readily observable without the requirement of

sophisticated testing equipment. As the patient gazes inferiorally, the apex of the cone angulates the lower

lid outward, forming a 'V-shaped' protrusion. Milder

signs of Munson's may be more easily seen when the head

is tilted slightly back and upper lids are lifted while

the patient gazes downward.

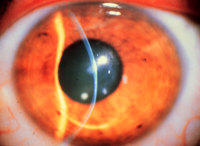

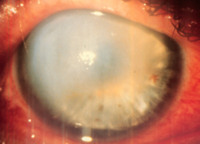

Corneal Hydrops -

usually seen in more advanced cases of keratoconus;

occurs when Descemet's membrane (a layer within the

corneal strata) is stretched beyond its breaking point

and ruptures. The influx of fluid from the aqueous

results in significant corneal edema and opacification (a

whitish-opaque spot appears on the cornea). Hydrops can

cause severe pain and significantly reduced vision.

Descemet's membrane regeneration is slow. As the membrane

layer regenerates, the edema and opacification gradually

resolve, but a scar formation will often remain on the

cornea. In some cases, hydrops can occur suddenly while

rubbing the eye.

KERATOCONUS

Keratoconus has no known cure, and

many people do not even know they have it because it begins as nearsightedness

and astigmatism. It is a progressive disorder that may progress rapidly or

sometimes take years to develop. It can severely affect the way we see the

world, including simple tasks such as driving, watching TV, or just reading a

book. Some keratoconus patients have described their vision as being “blind

with light.”

Keratoconus is a non-inflammatory,

self-limiting ectasia of the axial portion of the cornea. It is characterized by

progressive thinning and steepening of the central cornea. As the cornea

steepens and thins, the patient experiences a decrease in vision which can be

mild or severe depending on the amount of corneal tissue affected.

Onset of keratoconus occurs during

the teenage years--mean age of onset is age 16 years--but onset has been

reported to occur at ages as young as 6 years. Keratoconus rarely develops after

age 30 years. Keratoconus shows no gender predilection and is bilateral in over

90% of cases. In general, the disease develops asymmetrically: diagnosis

of the disease in the second eye lags about five years after diagnosis in the

first. The disease process is active for about five to 10 years, then it may be

stable for many years. During the active stage, change may be rapid.

Typically, vision loss can be

corrected early by spectacles; later, irregular astigmatism requires optical

correction with rigid contact lenses. Contact lenses provide a uniform

refracting surface and therefore improve vision. Contact lenses can improve

vision, but they can also scar the cornea. Patients should be informed upon

diagnosis that they will likely require contact lenses eventually. Although most

patients can continue to read and drive, some feel quality of life is adversely

affected. Patients need to know that eye examinations will be required annually

or more frequently to monitor progression. About 20% of patients will eventually

need a corneal transplant.

Etiology

The proposed etiology of

keratoconus includes biochemical and physical corneal tissue changes, but no one

theory fully explains the clinical findings and associated ocular and non-ocular

disorders. It is possible that keratoconus is an end result or final common

pathway of many different clinical conditions. It has been found in association

with hereditary predisposition, atopic disease, certain systemic disorders, and

long-term rigid contact lens wear.

Diagnosis

Identifying moderate or advanced

keratoconus is fairly easy. However, diagnosing keratoconus in its early stages

is more difficult, requiring a thorough case history, a search for visual and

refractive clues and the use of instrumentation. Often, keratoconus patients

have had several spectacle prescriptions in a short period, and none has

provided satisfactory vision correction. Refractions are often variable and

inconsistent. Keratoconus patients often report monocular diplopia or polyopia

and complain of distortion rather than blur at both distance and near vision.

Some report halos around lights and photophobia.

Many objective signs are present

in keratoconus. Retinoscopy shows a scissoring reflex. Direct ophthalmoscopy may

show a shadow (Fig. 1). If the pupil is dilated and a +6.00 D

lens is in the ophthalmoscopic system, the cone may appear as an oil or honey

droplet when the red reflex is observed.

Fig 1.

The keratometer also aids

diagnosis. The initial keratometric sign of keratoconus is absence of

parallelism and inclination of the mires. These can easily be missed in mild or

early cases. As the cornea advances, the mires appear smaller. To extend the

range of the keratometer, an ancillary lens is placed on the front of the

keratometer . If a +1.25 D lens is used, this extends the range to 60 D. To

record a reading, 8 D is added to the drum reading (for example, if the drum

reads 45 D, adding 8 D yields an actual reading of 53 D). A +2.25 D lens extends

the range to 68 D by adding 16 D to the reading.

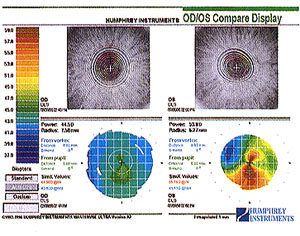

The photokeratoscope or

topographer placido disc can provide an overview of the cornea and can show the

relative steepness of any corneal area. Figure 2 depicts the

keratoconic cornea. The even separation of the rings in the spherical and the

astigmatic cornea and the uneven spacing of the rings--especially inferiorly--in

the keratoconic cornea should be noted. The central rings may show a tear-drop

configuration termed "keratokyphosis".

Reduced visual acuity in one eye,

due to the disease's asymmetry, may be a clue with the early keratoconus

patient. This sign is often associated with oblique astigmatism. In early

keratoconus, the patient may become less myopic six months later as the

astigmatism increases.

|

|

| Normal

keratoscopy |

Early keratoconus |

|

| Moderate

keratoconus |

Keratoconus can result in

extremely complex and variable topographical maps, most typically showing areas

of inferior steepening. The cone can assume various shapes and sizes, and the

apex can be at various locations in relation to the central cornea.

Placido's computerized video

topography showing unilateral early keratoconus

SLIT-LAMP DETECTION

The biomicroscope is the only tool

which allows a clinician to observe many classical signs of keratoconus:

Fleischer's ring, stress lines of Vogt, corneal thinning and scarring, various

types of staining with and without lens wear, increased visibility of corneal

nerves, and corneal hydrops.

Fleischer's Ring

The Fleischer ring is a

yellow-brown to olive-green ring of pigment which may or may not completely

surround the base of the cone (Fig. 3). Formed when hemosiderin

(iron) pigment is deposited deep in the epithelium , Fleischer's ring often

becomes thinner and more discrete with progression. A careful inspection of the

keratoconic cornea will reveal a line in approximately 50% of all cases.

Locating this ring initially may be made easier by using a cobalt filter and

carefully focusing on the superior half of the cornea's epithelium. Once

located, the ring should be viewed in white light to assess its extent.

Fig 3.

Lines of Vogt

Lines of Vogt are small and

brushlike lines, generally vertical but they can be oblique. These lines can be

found in the deep layers of the keratoconic stroma (Fig. 4) and

form along the meridian of greatest curvature; the lines

disappear when gentle pressure is exerted on the globe through the lid. Lines of

Vogt are more easily viewed when they reappear after this pressure is removed.

Rigid lens wear sometimes accentuates the lines. In advanced cases of

keratoconus, posterior corneal folds may also be present.

Fig 4.

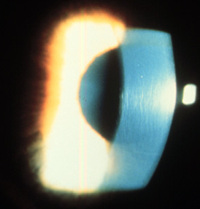

Corneal Thinning

Significant thinning (up to 1/5th

cornea thickness) in the advanced stages of the disease (Fig. 5),

and a diagnostic criterion based on comparison of central and peripheral corneal

thickness has been proposed. Additionally, as the disease progresses, the cone

is often displaced inferiorly. The steepest part of the cornea (apex) is

generally the thinnest. Apical thinning described is believed to represent an

actual reduction in the number of stromal lamellae rather than an overall

thinning process.

Fig 5.

Corneal Scarring

Sub-epithelial corneal scarring,

not generally seen early, may occur as keratoconus progresses because of

ruptures in Bowman's membrane which is then filled with connective tissue (Fig.

6). Deep opacity of the cornea are not uncommon in keratoconus. It has

also been reported that flat-fitting contact lenses may produce or accelerate

corneal scarring. A raised "callous" is possible but is easily treated

by simple debridement or laser ablation. In addition, apical scarring with an

overlying epithelial defect and surrounding edema can be confused for ulcerative

keratitis in this disease process.

Fig 6.

Swirl Staining

Swirl staining may occur in

patients who have never worn contact lenses because basal epithelial cells drop

out and the epithelium slides from the periphery as the cornea regenerates.

Thus, a hurricane, vortex, or swirl stain may occur (Fig. 7).

Swirl staining may be due to rubbing of the eye or can also result from flat-

fitting contact lenses. When this is the case, the lens is generally too flat. A

steeper lens often diminishes staining.

Fig 7.

Hydrops

Corneal hydrops occurs, generally

in advanced cases, when Descemet's membrane ruptures, aqueous flows into the

cornea and reseals (Fig. 8). Keratoconus patients who are

having an acute episode of corneal hydrops report a sudden loss of vision and a

visible white spot on the cornea. Corneal hydrops causes edema and opacification.

As Descemet's regenerates, edema and opacification diminish. Occasionally,

hydrops can benefit keratoconus patients who have extremely steep corneas. If

the cornea scars, a flatter cornea often results, making it easier to fit with a

contact lens. An increased incidence of hydrops has also been reported in

keratoconus patients with Down's syndrome. Excessive rubbing should be

discouraged in this population. Anecdotally, hydrops seemed to be more prevalent

when scleral lenses were employed as a treatment option.

Fig 8.

Munson's Sign

Munson's sign is readily

observable without using the slit lamp (Fig.9). This sign

occurs in advanced keratoconus when the cornea protrudes enough to angulate the

lower lid during inferior gaze.

Fig 9.

Ruzutti's Light Reflex

A light reflex projected from the

temporal side will be displaced beyond the nasal limbal sulcus when high

astigmatism and steep curvatures are present. Although not a pathognomonic sign,

Ruzutti's reflex may aid in a diagnosis especially when a biomicroscope or other

tools to aid in diagnosis are not available.

Reduced Intraocular Pressure

A low intraocular pressure is

generally found. This is a result of a thinner cornea and/ or reduced scleral

rigidity. Due to possible artifact and since the reliability of readings are in

question caution must be taken in carefully observing nerve fiber layers and the

overall health of the optic nerve.

Classification

Keratoconus can be classified by

cone shape, central keratometric reading, or progression. The simplest

classification systems are based on keratometric reading or shape:

Based on severity of curvature

Based on shape of cone

Surgical Treatments

Various types of surgery are

available for the patient with keratoconus. Penetrating keratoplasty

is the most common. In this procedure, the keratoconic cornea is prepared by

removing the central area of the cornea, and a full-thickness corneal button is

sutured in its place Usually, trephines between 8.0-8.5 mm are used. Fleischer's

ring can be used as the limit of the conical cornea. Generally, the second eye

is not grafted until the first eye is successfully rehabilitated. Running

sutures, using Merseline, anchored by cardinal sutures provide excellent results

(clear, compact grafts). Older patients with a slower healing response and

altered tear film generally do better with nylon and interrupted sutures for

selective removal. Contact lenses are often required after this procedure for

best visual correction.

An alternative is lamellar

keratoplasty, a partial corneal transplant. The cornea is removed to

the depth of posterior stroma, and the donor button is sutured in place. This

technique is technically difficult, and visual acuity is inferior to that

obtained after penetrating keratoplasty. As a result, use of lamellar

keratoplasty is largely confined to the treatment of large cones or keratoglobus

when tectonic support is needed. This technique requires less recovery time, and

poses less chance for corneal graft rejection or failure. Its disadvantages

include vascularization and haziness of the graft.

· Corneal Transplant

When good

vision can no longer be attained with contact lenses or

intolerance to the contact lens develops, corneal

transplantation (penetrating keratoplasty) is recommended.

In this procedure, the central area of the keratoconic

cornea is removed, and a full-thickness donor corneal

button is sutured in its place. Contact lenses are often

required after this procedure for best visual correction.

An

alternative is lamellar keratoplasty,

a partial corneal transplant. The cornea is removed to

the depth of posterior stroma, and the donor button is

sutured in place. This technique is technically

difficult, and visual acuity is inferior to that obtained

after penetrating keratoplasty. As a result, use of

lamellar keratoplasty is largely confined to the

treatment of large cones or keratoglobus when tectonic

support is needed. This technique requires less recovery

time, and poses less chance for corneal graft rejection

or failure. Its disadvantages include vascularization and

haziness of the graft.

For patients

with no scarring near the center of the cornea and 20/40

vision or better with contact lenses, another option is

surgically grafting a layer of epithelial cells to

flatten the cone-shaped cornea. This process is called epikeratophakia.

It has comparable results to corneal transplantation and,

if unsuccessful, it can be followed with corneal

transplantation.

· Corneal Implants

Intrastromal

corneal ring segments (INTACS) are currently being studied as an

option for the treatment of decreased vision in

keratoconus patients. INTACS are implanted into the

periphery of the cornea, producing a flattening effect to

the central cornea that results in a smoother contour of

the corneal surface. The advantage to INTACS is that the

ring segments can be removed should any adverse effects

arise following the implant procedure, or if improved

vision is not successfully obtained.

· Laser

Excimer laser

procedures may have some potential merit, having been

used recently with some success in removal of nodular

"callous" plaques of the central cornea. New

developments in excimer corneal modeling may allow

lamellar onlay or penetrating grafts to be lathed,

thereby eliminating refractive ametropia following

various surgical procedures.

THE GENETICS OF KERATOCONUS

In the keratoconic cornea, a possible genetic

predisposition to increased sensitivity to apoptotic

mediators by keratocytes has also been hypothesized.

Click

here for Keratoconus

Statistics

Sources

* Yuksel Totan, Osman Cekic, Erdinc

Aydin. Incidence of keratoconus in subjects

with vernal keratoconjunctivitis: A videokeratographic

study. Ophthalmology 2001; 108:824-827.

* Wilson SE, Lin DTC, Klyce SD. Corneal

topography of keratoconus. Cornea 1991; 10:

2-8.

|